We face deep division in the U.S. about how to be a citizen. Core democratic values are being fought over. In the midst of heartbreak, chaos and fear over the threat to democracy in the U.S., the imperative to improve civics education cries for attention. We want to tell our story to inspire this generation of educators and students to connect with their deepest values and step into action as knowledgeable and compassionate citizens.

Looking back to our first job as junior high school teachers in the 70s and how the Law in Action civics curriculum came about, we are struck by the unexpected ways “life” stepped in to help us. Our deep desire for students to see their own potential as citizens led to results beyond our expectation. In retrospect, we see that our efforts were achieved in large part by circumstances greater than our own capabilities. We know now that what we, each person, chooses to do matters; and, that it’s awesome to watch for the assistance that shows up along the way. Looking back, we can see that doors opened for us to provide a kind of civics education that empowered students to see what they could do as caring and responsible citizens. Fifty years later, we find that we are still civics teachers at heart — we encourage you to align your deepest civic intentions with your best efforts and look for the positive help that comes your way.

Our Story

In 1970, we chose to teach social studies at the junior high level in St. Louis Missouri. We wanted students at that age to know that they mattered and that their participation was needed as citizens. As emerging adolescents they were just beginning to imagine the adults they could become. We wanted to help bring out the best in them.

In September 1970, we were completing student teaching requirements. We didn’t know each other but fortuitously Washington University in St. Louis paired us up to teach 8th graders at Hamilton Elementary School in St. Louis. Established in 1918, Hamilton Elementary was an impressive three story brick building serving a neighborhood in the West End of St. Louis. Almost all the students and teachers were African American. Our classes had over 35 students. Our assignment for the semester was to teach civics using a book about St. Louis city government and one about the U.S. Constitution. We were shocked with the dull photos, unimaginative images and that the text was well above reading level for most of the students. The information made civics boring and distant. There were no participatory activities and no questions that asked the students for their ideas and opinions. A particularly disturbing page described some city neighborhoods (some that were near Hamilton School) as “blighted.” We understood that a “blighted neighborhood” meant one that had once been functioning well but had fallen into disrepair and decrepitude.

Driving to school together, our daily conversations convinced us that learning civics from these books would push our students away from seeing themselves as valuable citizens. The students deserved better! We spent hours after school and most weekends considering what kinds of lesson ideas would work best with the student’s abilities and interests. One teacher affirmed that our lessons worked because they took into consideration the students’ life experiences and could help students beyond the classroom.

When we introduced “city services” as part of local government studies, the students described various problems in the neighborhoods, but there was one that was personal to them. They said they were mad because a nearby roller-rink had closed. It meant no roller skating during their 8th grade year. A big disappointment! They explained that it was expensive to go to the roller rink across town using public transportation. We asked was there something they could do about it. After some discussion, the classes came up with an idea to get their own bus transportation. We involved the students in writing a proposal. Their plan included: facts about the Skate Club they would form, commitments from parents and teachers to chaperone, the reason transportation was needed, and a budget for a bus and a bus driver. In the midst of the action, one student sat sullenly, arms folded tight. She pouted, “this is a waste of time, no one will listen to us.” A fire burned in me and I roared back, “it is about time they start!!” The students were all in. In a few weeks, a neighborhood church responded to the proposal, offering its own church bus and bus driver. The principal, teachers and parents approved. The proposal was a success! The students had worked together to find a solution to meet their need. We were fired up that civics learning must include responsible action.

Engaging Students

Rather than memorizing the Bill of Rights from the U.S. Constitution, students were asked to think about the rights and freedoms that these laws protected. Students were invited to put themselves in the shoes of Supreme Court judges who grappled with hard questions when people’s rights came into conflict. We told students that not only judges, but all people including them, were needed to figure out what is fair. Students studied actual Supreme Court cases. They sat in small groups, identified the facts, found the issues, and made arguments. They had to make a decision and back it up with their reasons. Once during a heated discussion, one student got out a handkerchief, rubbed his head, and said, “my brain is sweating I’m thinking so hard!”

Students shared real problems: a brother harassed by police, a store closing because of so much shoplifting, and TVs “on sale” that were not really sales at all! We heard about young people inhaling turpentine fumes to get high, bikes getting stolen, problem of stray dogs and garbage in the streets. There was general mistrust of police, ignorance about how to get help from city services, and little understanding that the legal system could be used to help them. The students needed helpful information about legal issues that impacted their lives. To fill this need, we invited lawyers from the St. Louis Legal Aid Society to speak with our classes. They taught our students (and us) about practical laws that the students cared about. One lawyer helped us write a grant asking for funds to develop practical law-focused curriculum and train teachers. Our student teaching term ended, we got the grant, and began to work out of an office at the Legal Aid Society. We were invited by the St. Louis Public Schools to co-teach our lessons with teachers in schools across the district. We called the burgeoning body of lessons, Law in Action.

Dr. Isidore Starr – A Remarkable Mentor Shows Up

In summer 1971, we went to Chicago to attend a teacher training course called Law-Related Education. Mornings were devoted to legal issues taught by lawyers, afternoons to teaching methods. One professor, Dr. Isidore Starr, taught both the law and education sections. Dr. Starr (Iz) fueled our passion to teach about law, not as lawyers need to learn it, but as citizens need to participate in it. Iz’s enduring respect for the rule of law empowered us to use law to teach principles of democracy. As our mentor, Iz taught us about the law, but most of all he gave us what we wanted to give students – assurance that their contribution mattered. In the following decades, Iz catalyzed the development of a vibrant new field in social studies called Law-Related Education. Iz came into our lives at the perfect time and remained a mentor and life-long friend. At his 100 year birthday party, we gathered with law-education teachers from across the country, to honor and celebrate Iz. He had hired his favorite band — Iz danced the night away with us.

Doors Opened to Publish

An assistant at the Legal Aid Society, Margaret Neuwirth, was new in town. Margaret had previously worked in publishing in New York City. She offered to put together a prospectus for Law in Action and send it to publishers. We were grateful for her kind offer, and had no idea what might happen.

Two marketing men from West Publishing Company (the biggest law book publishing house in the world) heard Linda present at an American Bar Association (ABA) legal education conference. They were looking to fill gaps in civics curriculum at the junior high level. They recognized our innovative approach to teaching civics reflected the real life needs of students.

We reached out to juvenile judges, university professors, law enforcement officers and legislators to help us refine the content. We put in long hours of writing and rewriting to discover ways to explain the deeper concepts of law to students. What exactly is “due process of law”? When “how the law should be” does not a match with “what actually happens,” how do students learn to deal constructively with these discrepancies?

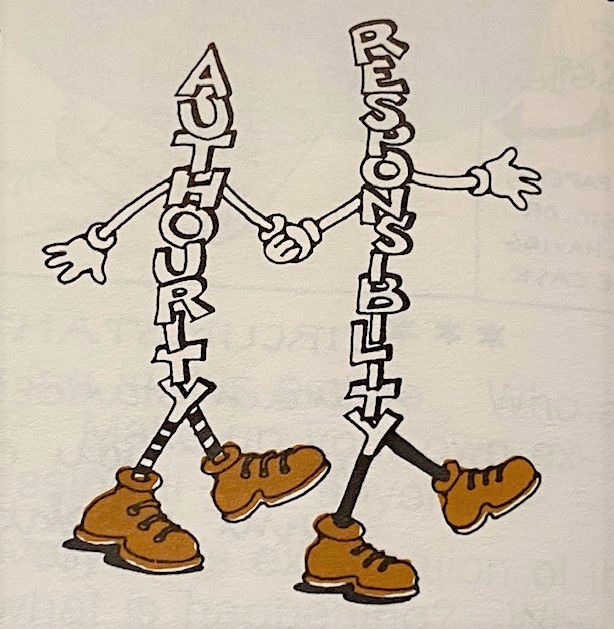

We believed that how civics was taught was as important as what was taught. We wanted images that encouraged students to see themselves in the lessons. We wanted visuals that helped explain difficult concepts.

Mary Engelbreit Illustrator

We had begun working with the director of a graphics firm in St Louis’ Central West End. One day the director took off without notice leaving us stranded. Mary Engelbreit, who was a college student at the time, was working there. Mary understood that we needed civics books with the liveliest illustrations ever. She said, “I can give you what you need.” Mary, who became a renowned artist and designer, provided illustrations that resonated with students and piqued their curiosity.

Law in Action Series

West Publishing had never published a book with illustrations much less pages filled with Mary Engelbreit’s imaginative creations. Our editor at West adored this creative opportunity – with exuberance and kindness, he worked along with us designing each page with care. Our efforts came together in a five book series published in 1975, with a second edition published in 1980. View the images here

After the books were published, we spent the next several years traveling across the United States engaging teachers in action-oriented lessons that they could use with their students. Mary’s illustrations added meaning, spirit and fun. The lessons involved students in authentic civic experiences which reinforced their role as citizens in a democracy.

Reflection

Our story is about the power of passionate intention to make a positive difference. Unabashedly, we acknowledge the unexpected openings and people who helped us make Law in Action an effective curriculum that lit up teachers and students. Looking back, we are grateful for the forces beyond our efforts that brought us together, that opened doors and guided us as we took one step after another.

Times are different now, but the critical need to empower one another to act with civic responsibility is the same. Civic responsibility is uniquely personal, ready to be fired up inside of us, and bursting with creative solutions. When we choose to get into the action representing justice, equality, freedom, truth and compassion, we have already changed things for the better. Every inspired intention, effort and action counts.

—

Linda Riekes worked for the St. Louis Public Schools for over forty years developing a variety school and community programs and securing resources. She lives in the city of St. Louis.

Sally Mahé worked for over 25 years developing an international grassroots peacebuilding organization and co-authored, A Greater Democracy Day by Day. Sally lives in northern California